|

excerpts from An Intellectual

History of Modern Europe by Marvin Perry The Scientific Revolution: A New Cosmology and Methodology

The Scientific Revolution made the medieval world picture obsolete and

established the scientific method, rigorous

and systematic observation and experimentation, as the means of unlocking

nature’s secrets. Natural philosophers finally grasped the essential

importance of mathematics to understanding the natural world, and this tool

would grow more sophisticated with the discovery of the calculus. These early

scientists conceived of the universe as a mechanical system governed by

mathematical laws. Science displaced theology as the queen of knowledge and

gave rise to the Enlightenment. The Origins of the Scientific

Revolution

Medieval thinkers, influenced by Plato and Aristotle, had conceived of the

cosmos as a divine hierarchy with the earth at the center but lower than the

heavens. This dualistic model of the universe divided into higher and lower

worlds accorded with passages of Scripture that medieval scholastic

philosophers had cited to harmonize classical science with Christian

theology. Aristotle’s Model of the

Universe

Human beings, at the center of the universe and in the center of the great

ladder of creation, were the masters of Earth. Earthly objects were composed

of the four elements: earth, air, fire and water; celestial objects were

composed by a magical ether. The planets, according to Ptolemy, the ancient

astronomer, moved in perfect circular orbits and at uniform speeds around the

earth. Since the planets do not move in circles, but ellipses, Ptolemy, had

been forced to invent complicated explanations of these apparent

eccentricities (epicycles, equants, and retrograde motion) to save the

appearance of circular motion. Aristotle’s Theory of the

Solar System (Video) The Renaissance paved the way for the Scientific Revolution. Revived interest in classical science had led to the rediscovery of important ancient texts (Archimedes’ mechanics and Galens’ anatomy). Artists’ representations of the human body linked exact proportions to a principle of beauty. Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) formulated the mathematical theory of perspective in his depiction of space, establishing a precise mathematical relation between the object and the observer. The natural world could now be analyzed and depicted with scientific precision.

The revival of ancient Pythagorean and neo-Platonic ideas led to a new stress

on mathematics as the key to the comprehension of reality. The Pythagoreans

had been fascinated by the mathematical harmonies to be found in music. They

extended this idea to the universe at large, expressing the idea that

everything in nature could be expressed numerically. They believed that

knowledge of this cosmic harmony could purify the soul. (Music of the Spheres)

Plato had maintained that beyond the world of everyday objects lay a higher

reality, the world of Forms, which contains a mathematical reality

apprehensible only through rational thought. Renaissance science blended

science with mysticism and magic in the tradition of Hermes Trismegistus,

thought to have been an Egyptian priest and contemporary of Moses. The

Hermetic writings mixed astrology, alchemy, Jewish creation accounts, and

mystical yearnings with neo-Platonism and Pythagoreanism. Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543)

This astronomer and mathematician proclaimed that the earth is a planet that

orbits a centrally located sun together with the other planets. The

heliocentric theory became the kernel of a new cosmology. Copernicus’

sense of mathematical order had been offended by the cumbersomeness of

Ptolemy’s model of the universe. His theory was published in 1543, but his

ideas had become current even earlier than that.

In 1539 Martin Luther condemned Copernicus, but his astronomical

theories did not inspire passionate rejection until the religious wars of the

early seventeenth century. In 1616 the Catholic Church banned

Copernicus, fearing another propaganda weapon for Protestants. Authorities

feared the theological and social implications of Copernicus’ reordering of

the cosmos in opposition to the divisions of the divine hierarchy.

This new cosmology inspired some religious thinkers to develop new

conceptions of God. Giordano

Bruno (1548-1600) was burned at the stake for heresy because he had

embraced Copernicus’ theory and combined it with mystic hermeticism to

conceive of the universe as a living creature existing in an infinite space

which must contain innumerable inhabitable worlds. To Bruno, nature was God,

worthy of worship and investigation. He believed this new religion of

rapturous worship, glorification and contemplation of nature should replace

the teachings of organized churches.

Contemplation of the new cosmology could also produce despair. Instead of a

secure universe created for man, Copernican astronomy dethroned man, expelled

human beings from their central position in the cosmos, and implied an

infinite universe. This concept would prove as traumatic for modern thinkers

as Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden had been for medieval thinkers. The

Copernican Model (Diagram) Galileo's Drawing of the Moon

Indebted to the Platonic tradition of mathematics and to Archimedes’

mechanics, Galileo exploited the recent invention of the telescope

to prove Copernicus’ theories scientifically and to advance a new

understanding of physics. (Galileo’s

Telescope) His observations of craters and mountains on the moon and of

spots blemishing the surface of the sun proved that the celestial bodies were

not perfect and immutable. (Galileo's

Drawing of the Craters on the Moon)

(Sunspots)

This demonstration showed that all of nature was a homogeneous system, not

hierarchical. His observations of the moons of Jupiter demonstrated that a

celestial body could indeed move around a center other than earth. In dealing

with problems of motion, Galileo dispensed with Aristotle’s ‘common sense’

conclusions and insisted on the application of mathematics to experiments.

Instead of concluding that rocks fell to earth because they were striving to

reach their proper place in the universe, Galileo insisted that motion is a

mathematical relationship of bodies to time and distance. Galileo

and the Mathematics of Motion

Galileo’s experiments and discoveries attacked the authority of the

Scriptures in scientific matters. He tried to separate science from faith. He

argued that the purpose of Scripture was the salvation of the soul, not the

instruction of people in the operations of nature.

In 1633 Galileo, under the threat of the Inquisition, was forced to recant

and condemn the theories of Copernicus. One of the consequences of the

Church’s stand was the impetus it gave to the study of science in the

Protestant areas of Europe. The

Surface of Jupiter (animation) The Galileo Project (Rice

University)

This German mathematician and astronomer was deeply influenced by the

teaching of Renaissance Pythagoreans and neo-Platonists. He tried

to harmonize mathematics with a deep commitment to Lutheran Christianity. He

believed that God had prescribed a geometric harmony to creation which humans

could understand. He was also a believer in astrology. He yearned to

understand the ‘music of the spheres’ and thus achieve a supreme insight into

God’s mind. Even so, he did not allow the inspiration of his mystical beliefs

to obscure his disciplined dedication to empirical research.

Using data collected by a Dutch astronomer, Tycho Brahe, Kepler

discovered the three basic laws of planetary motion. First, planets move in

an elliptical orbit with the sun at one focus of the ellipse. Second, the

planets do not move at a uniform speed; instead he argued that they

accelerate as they approach the sun. A planet’s speed is determinable at any

point since its arc will sweep out an equal area of space in equal areas of

time if a line is drawn from the planet to the sun. Third, there is a

mathematical relationship between the time it takes a planet to complete its

orbit of the sun and its average distance from the sun: time squared is

proportionate to distance cubed.

Kepler’s

Laws of Planetary Motion

Isaac Newton provided the celestial mechanics that linked the astronomy of

Copernicus and Kepler with the physics of Galileo and accounted for the

behavior of the planets. His publication of The Mathematical Principles of

Natural Philosophy in 1687 climaxed the scientific revolution and

arguably can be described as the birth of the Enlightenment. Newton’s three

laws of motion joined all celestial and terrestrial objects into a vast

mechanical system which functioned in perfect harmony and whose connections

could be expressed in mathematical terms. He offered mathematical proof of

the heliocentric system.

The Laws of Motion: Newton’s first law is the

principle of inertia: a body at rest remains at rest unless acted on by a

force, and a body in rectilinear motion moves in a straight line at the same

velocity unless a force acts on it. Motion is as natural a condition as rest.

The second law states that a given force produces a measurable change in a

body’s velocity, the change in velocity proportional to the force acting on

it. The third law holds that for every action or force there is an equal and

opposite reaction or force. The sun pulls the earth with the same force that

the earth pulls the sun.

Newton proved that the same laws of motion and gravitation that operate in

the celestial world also govern the movement of earthly bodies. There is no

cosmic division, no dual universe. The universe is an integrated, harmonious

mechanical system held together by the force of gravity. His laws

demonstrated the inherent mathematical order of the universe, thus realizing

the ancient Pythagorean and Platonic visions of the cosmos.

Many of Newton’s contemporaries believed he had unraveled all of nature’s

mysteries. For Newton, God was the grand architect whose wisdom and skill

accounted for nature’s magnificent design. Newton believed that God could

intervene in this clockwork universe and perform miracles. Later, followers of

Newton, the deists, would reject miracle as incompatible with a

universe governed by impersonal mechanical principles.

Newton helped formulate the scientific method: a systematic and logical

process of inquiry into the properties of phenomena on earth and establishing

those properties by experiment, only then proceeding to hypotheses for

explanations of the phenomena themselves. Newtonian

Mechanics With Gravity Francis Bacon (1561-1626): The New Empiricism

Sir Francis Bacon, an English statesman and philosopher, was an important

advocate of the scientific method. In his New Organon (1620), Bacon

repudiated the medieval scholastics' effort to blend theories of nature with

the requirements of Holy Scripture. He denounced scholasticism’s slavish

attachment to Aristotelian doctrines because that prevented independent

thinking. He also complained that the arid, pure verbal ingenuity of the

scholastics’ elaborate arguments had little or nothing to do with the

empirical world. Bacon argued that humans needed to resist their tendency to

color observations of nature with prejudices from their experience, their

desire for profit, or their attachment to any philosophical dogma. Instead,

Bacon advocated inductive reasoning as the path to truth. Through

careful observation of nature and the systematic accumulation of data,

general laws could be discovered from the knowledge of particulars. These

laws should be constantly tested and verified by experimentation. Bacon

became a founder of the empirical tradition in modern philosophy. He attacked

astrology, magic, and alchemy. He advocated cooperative and methodical

scientific research that could be publicly criticized. Bacon appreciated

science’s potential value for human life. The function of thought was not to

explain how everything fit into a divine design; rather, knowledge should

help us utilize nature for our own advantage and improve the quality of life. Rene Descartes (1596-1650) The New Rationalism

Rene Descartes, a French mathematician and philosopher, developed the other

approach to knowledge which underlay the scientific method: deductive

reasoning. Whereas Bacon regarded sense data as the foundation of

knowledge, Descartes believed that truth derived in successive steps from

first principles, indubitable axioms. In his Discourse on Method

(1637), Descartes rejected all authority for knowledge which depended on the

senses which he revealed as fallible. In one famous argument, he considered a

piece of wax. Using his senses he could measure a piece of wax's various

physical characteristics: its shape, size, weight, texture, etc. However,

when he melted the wax using a flame, the substance possessed utterly

different characteristics. Even so, his mind knew that the substance remained

wax. Descartes therefore concluded that the mind, not the senses, was

essential to knowing.

Descartes searched for one incontrovertible truth that could serve as the

first principle of knowledge, and he found one truth to be certain and

unshakeable: his mind was at work: "Cogito ergo sum" (“I

think therefore I am.”) Here was the starting point of knowledge. By

overthrowing all authority for thought except the individual’s inviolable

autonomy and importance, Descartes founded modern philosophy. Human beings

had become fully aware of their capacity to comprehend the world with their

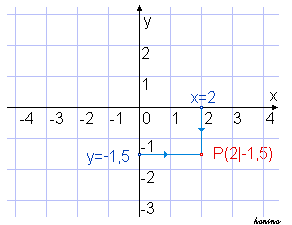

own mental powers. The

Cartesian Plane

Descartes was a brilliant mathematician who founded

analytic geometry, the bridge between algebra and geometry, crucial to the

invention of calculus. Descartes believed that mathematical reasoning could

be applied to philosophical problems, thus providing a geometry applicable to

the moral order. Once his central axiom (“I think therefore I am.”) was

accepted, other truths could be logically deduced. Proceeding step by step

from the fact of his own existence, Descartes was able to deduce the

existence of the physical world and the existence of God. Descartes argued that because humans could

conceive the idea of a perfect being, then God must exist. The idea of

perfection had been implanted in us. The conception of perfection presupposes

the existence of God. God ordered the universe in such a way that it

functions in harmony with the human mind, and He gave humans the capacity to

understand the world. Descartes argued that he structures of the natural

world correspond to the form of the ideas of the mind. Logic is not only

inherent in the human mind but also independent of human existence. Descartes reasserted Plato's dualistic

conception of the universe. He divided reality into two fundamentally

different substances: the mind

with its principle attributes of consciousness and thought, and matter which is characterized by spatial

extension. A basic question of modern philosophy has been the attempt to

discover where the mind and matter connect.

Although Descartes believed in God, he thought that once God had set the

universe in motion, he served no further significant function. His support of

reason and his faith in the ability of humans to think for themselves

undermined Christian dogma and helped form the skeptical outlook of the

Enlightenment. History of Philosophy:

Descartes Benedict Spinoza (1632-1677)

Rationalism

Spinoza was a descendant of Spanish Jews who fled to the Netherlands to

escape the Inquisition. He studied traditional Jewish religious and

philosophical works, medieval scholasticism and the new science and

philosophy of Descartes. He disputed rabbinical interpretation of the

Scripture, was accused of heresy, and subsequently was excommunicated by

Jewish religious authorities. He lived simply as a lens grinder and devoted

his life to philosophy.

Spinoza used the logic of mathematics to understand the world. He modeled his

metaphysical arguments on Euclidean geometry: first axioms and definitions

allow propositions to be deduced. If we accept the axioms, and the deductions

are properly made, then we must accept the conclusions. He took the same

approach to ethics. Like Descartes, he contended that reality was

intelligible only through reason. Applying the logic of Euclidean geometry to

philosophy, he began with what seemed to be universally valid premises and

deduced other truths using logic.

Spinoza held that the highest form of knowledge was the knowledge of God, but

his conception of God marked a radical break with traditional thinking. To

Spinoza, God was not a transcendent creature, some superhuman father

possessed of intellect and will. Inspired by the new science, Spinoza

identified God with the order of nature: a single, all inclusive system of

unchanging, universal laws in which all things have a determinate place.

Unlike Descartes who conceived of a sharp divide between thought and

substance, Spinoza believed that the universe was monistic: thought and

substance are different aspects of the same being. Since this unified system

is open to reason, divine revelation is unnecessary. Spinoza was a

determinist who believed that everything happens due to necessity: an

unbreakable chain of cause and effect. The only freedom humans possess stems

from our ability to understand our situation (ala Oedipus). Spinoza

called for a critical reading of the Bible as an ancient, human text that

should be analyzed using linguistic and historical techniques. He condemned

belief in miracles and in the efficacy of prayer as superstitions and

dedicated himself to scientific objectivity. He pleaded for freedom of

thought, religious toleration, and a constitutional government. Spinoza’s

thinking was a hallmark of the emerging modern mind. History of Philosophy:

Spinoza |